Modernist Pioneer: Charlotte Perriand

“Everything changes so quickly, and what is state of the art one moment won't be the next. Adaptation has to be ongoing – we have to know and accept this. These are transient times.” - Charlotte Perriand

Born: October 24, 1903, Paris, France

Died: October 27, 1999, Paris, France

Nationality: French

Partner: Jacques Martin (1942–)

French designer and architect Charlotte Perriand left her mark on 20th century design and society. © AChP. Photo: ARTE France

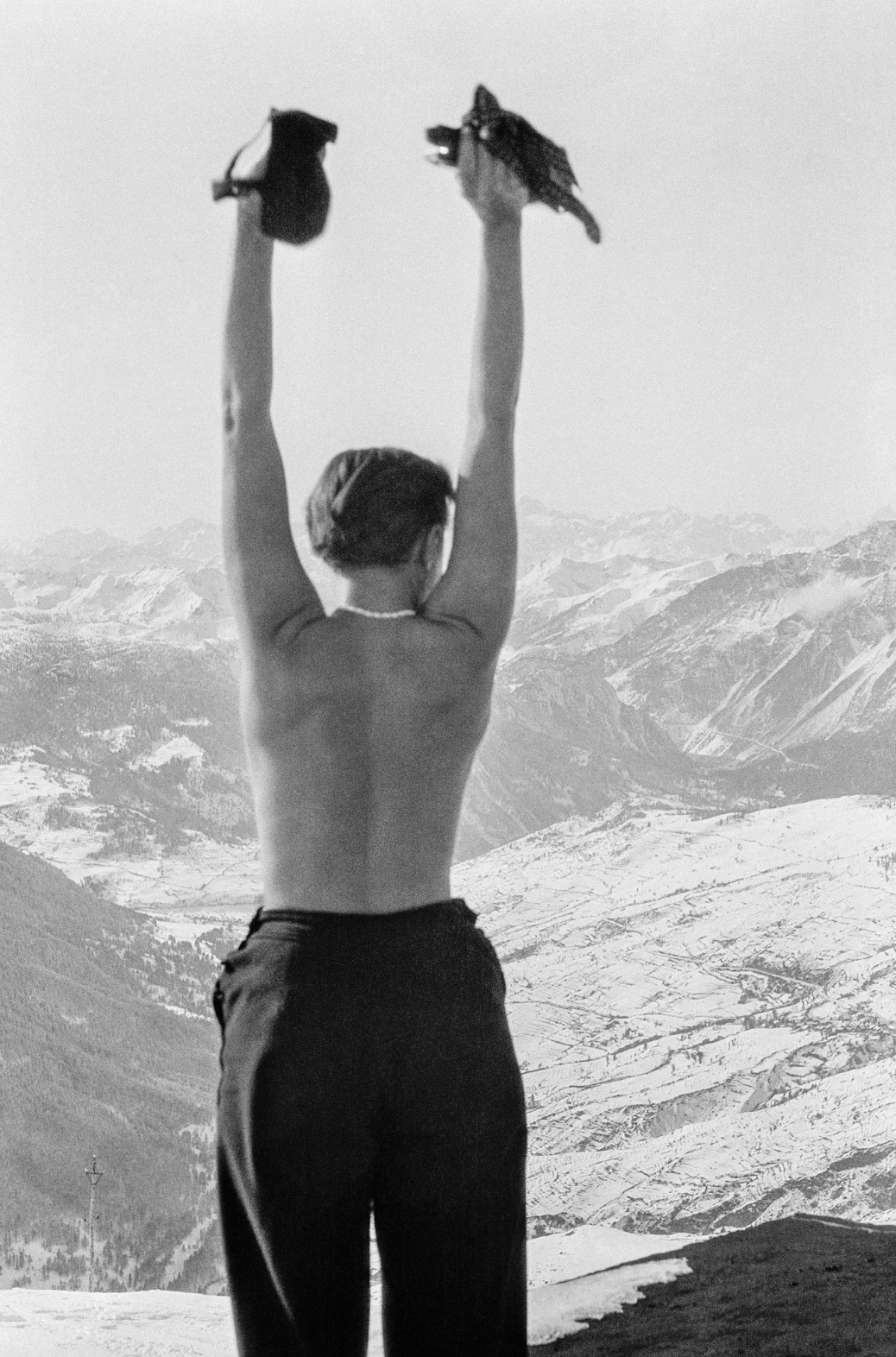

Perriand stands triumphant, facing a snowy mountain scene, in this 1920s image. © ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP

While many believe that Charlotte Perriand sits firmly as one of the most influential designers of her generation, it’s also true that many know very little about her history and how she rose to gain international recognition.

Charlotte Perriand was born in Paris in 1903. Her father worked as a tailor and her mother as a seamstress. During her childhood she traveled to Savoy, France, the remote mountainous region was like a second home to her and was where her paternal grandparents resided.

Throughout her adolescence she spent most of her time in the city. It’s where she lived and worked in and was inspired by. Perriand would also escape the stresses of the city and would return to the French Alps where she would enjoy herself, relaxing, skiing and taking in the regions natural beauty.

One of her many gifts was her drawing ability. It caught the eye of her junior-high-school art teacher who saw such talent, that he and Perriand’s own mother, urged her to attend the École de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs where she would study from 1920 to 1925. Beyond studying at school, she pushed herself harder and enrolled in more classes that were made available through large department stores. They housed their own design workshops and this gave Perriand her first taste of what it would be like to work at an atelier.

After graduating, Perriand knew she had to put herself out there in order to succeed. She began submitting her works to various exhibitions. At the time, wood was the primary material used for furniture design but Perriand preferred an aesthetic that mirrored the age of the machine. Opting for materials such as nickel and steel - a medium previously only used by men.

While beginning to gain recognition in the field, Perriand still had her own doubts about her work. She even expressed her anxiety to a close friend, Jean Fouquet, who suggested she read Le Corbusier’s books, Vers une architecture (1923; Toward an Architecture) and L’Art décoratif d’aujourd’hui (1925; The Decorative Art of Today). After reading, Perriand felt ready to tackle her next endeavor. She deeply resonated with Corbusiers writings, not only did they go against the decorative arts and everything she studied in school, but she felt in alignment with his approach to design.

Perriand arrived at Le Corbusier’s atelier, portfolio in hand but was dismissed and told “We don’t embroider cushions in my studio.” The 24 year old didn’t let that degrading comment lessen her drive to want to work for the revolutionary architect. She instead invited him to the Salon d’Automne to view her work. He attended and after seeing her work- he hired her on the spot.

This friendship would go on to change the history of the design world forever. Imagine if he never gave her a chance because she was a woman. Instead, he accepted her. He saw her potential and the rest is history.

For the next ten years, (1927-1937) Perriand would work at his atelier, later calling it a ‘privilege’. She worked on fabrication of prototypes up until final production. She famously contributed to the design of three iconic pieces, the LC1 easy chair (1928), the “Fauteuil Grand Confort” LC2 & LC3(1928), and the LC4 chaise lounge (1928).

With his towering reputation, Corbusier is often given sole credit for these famed designs. While Perriand acknowledged that Corbusier did lay out the framework and overall form, she was the one who was considering and paying close attention to details, construction and the ultimate design with Corbusier’s cousin, Pierre Jeanneret. It’s the work of these three individuals that should be given credit. Their designs are produced to this day by the Italian manufacturer Cassina who gives credit to all three designers.

After leaving Corbusier’s atelier, Perriand began working with Jean Prouvé.

The two both subscribed to the same belief system. Passionately expressing their craft through contemporary means and materials. Prouvé’s atelier became flooded with projects for the French army during the war, leading Perriand to design furnishings for temporary housing and even military barracks. In 1940 France surrendered leaving the team to disperse and go their own ways. In the spring of 1951 they would reunite again. Perriand would look back on these times with great fondness. She developed deep respect and a strong friendship with Prouvé.

Weeks prior, Perriand received an enticing invitation from the Japanese Embassy in Paris. Their Department of Trade Promotion needed expertise in industrial design. They were keen on placing a foreigner on the task, this would help them in their effort to increase the flow of Japanese products to the West. This move allowed her to challenge the status quo among Japanese and western artisans and consumers. On the day the Germans arrived to occupy Paris, June 15th 1940, Charlotte Perriand left France for Japan, boarding the Hakusan Maru to embark on a journey that would take two months and six days.

© AChP

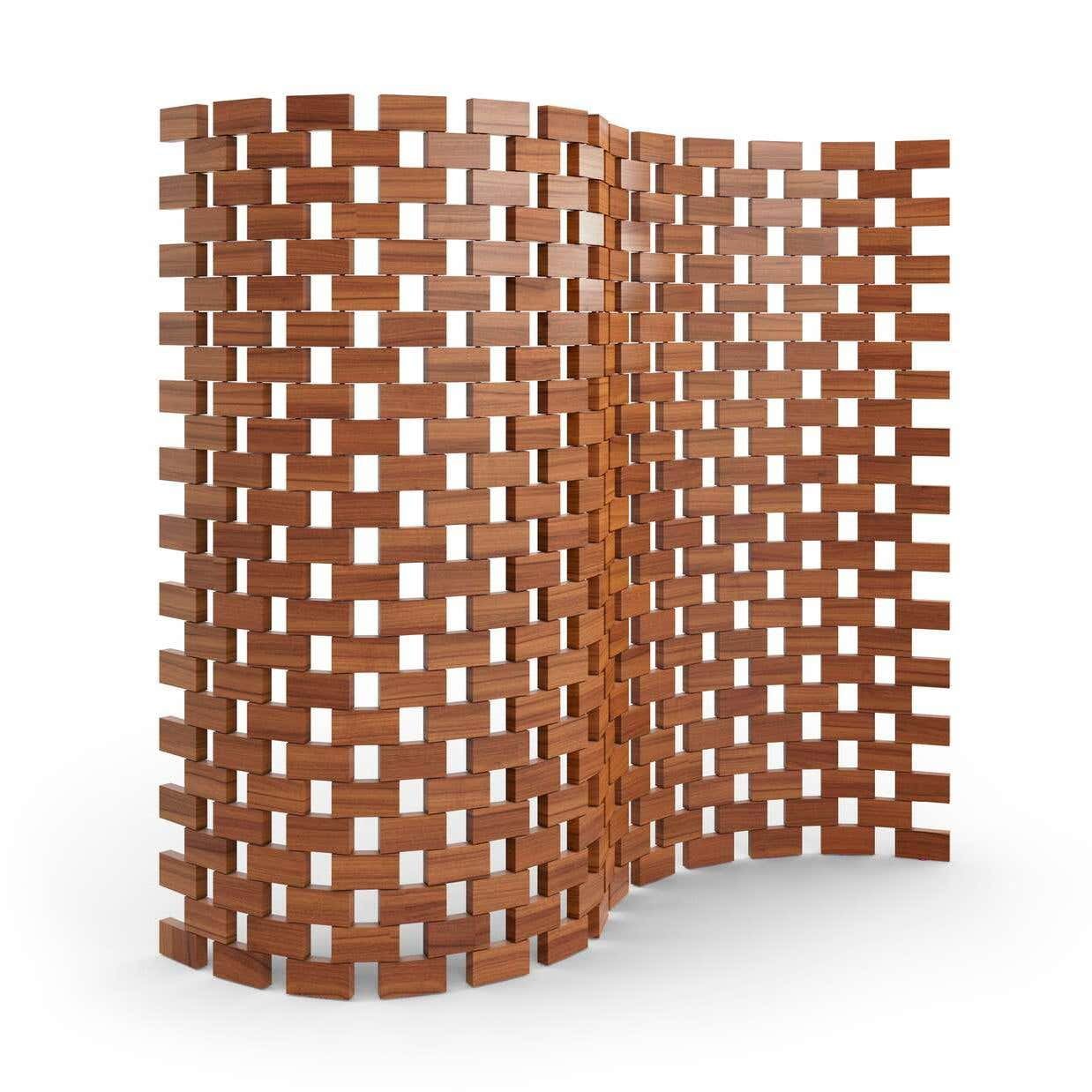

While her previous craftsmanship was indulged in machine age materials, Perriand found herself intrigued with Japans natural materials like wood and bamboo. She began to depart from the aesthetic that she had once honed at Corbusier’s atelier. She admired and engaged in the local artisans from traditional craftsmen to modern marvels. Overall, she received negative feedback as many Japanese wanted to move beyond the current materials and work in more progressive ways to be suitable for mass production. However, this didn’t deter Perriand. In fact she continued to return to Japan for many years.

Charlotte Perriand, Air France Agency, London, 1957. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Gaston Karquel / AChP.

Ultimately, she would go back to work with her former colleagues, Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Jean Prouvé who had large roles in the emergence of her career. But she also made sure to continue expanding her network and began to work with Fernand Léger, Brazilian architect Lúcio Costa, and Hungarian architect Ernö Goldfinger. She pursued jobs in various locations including the French Alps (1938), Unité d’Habitation in Marseille (1950) and Tokyo (1959) and Air France in London (1958). In the end, she returned to the landscape she remembered so fondly from her youth and completed her final and largest project, the ski resort of Les Arcs in Savoy (1967–85).

Charlotte Perriand’s work was very much inspired by the multitude of experiences and cultures she came to understand. She embraced the unknowing and rather than waiting for opportunity to find her, she found it. Overall, Perriand withstood harsh judgement and criticism from her male colleagues but still stood head-held-high and continued to push herself in the male dominated industry. By doing so, she managed to build an international reputation for herself and accomplished many things society told women they could not. Perriand passed away in 1999 at home in Paris, the place where her journey first began.

A quote I really love is from Justin McGuirk, the chief curator at the Design Museum who stated, “She didn’t just move with the times, she also shaped them.”

© AChP

WORK OF CHARLOTTE PERRIAND:

“Everything changes so quickly, and what is state of the art one moment won't be the next. Adaptation has to be ongoing – we have to know and accept this. These are transient times.”

-Charlotte Perriand

We have not included every work of Charlotte Perriand’s. We urge our readers to do their own independent research into all of her designs.

DISCLAIMER: THE MILLIE VINTAGE DOES NOT OWN ANY RIGHTS TO THESE PHOTOS. PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL IMAGES AND COPYRIGHT BELONGS TO THE ORIGINAL OWNERS. NO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT INTENDED.

It’s no surprise that celebrities have the ability to acquire some of the most rare and incredible pieces of design. We are thrilled to see faces we look up to, enjoying vintage design as much as we do.